PAS Agriculture webinar episode 4 entitled “A Review of Agriculture Policies of Pakistan/Policy Brief”

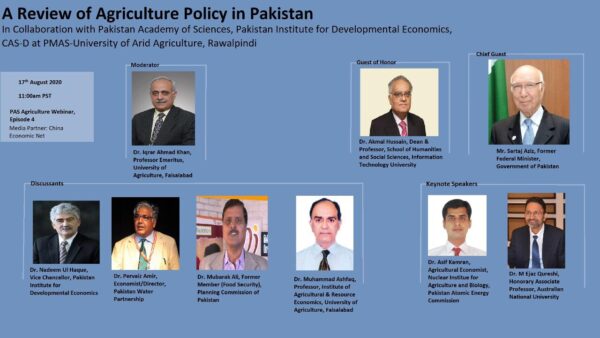

Prof. Dr. Iqrar A. Khan in collaboration with Pakistan Academy of Sciences (PAS), Pakistan Institute for Developmental Economics and CAS-D at PMAS-University of Arid Agriculture, Rawalpindi organized a zoom PAS Agriculture webinar episode 4 entitled “A Review of Agriculture Policies of Pakistan” on 17th, August 2020 at 11:00 AM PST

Agriculture policy framework in Pakistan has remained a high priority with successive governments. As summarized in the 1988 Agriculture Commission report by Mr. Sartaj Aziz, we have had a continuous flow of policies and plans. During colonial rule, a Famine Commission was established in 1879 which had drawn pathways for irrigated agriculture. That was followed by a continuous flow of policy input to keep agriculture afloat. The first major post-partition attempt was the Agriculture Commission of 1959 led by Malik Amir Muhammad Khan, Nawab of Kala Bagh. It was the implementation of the Kala Bagh recommendations (Government of Pakistan, 1960) that enabled the country to adapt for green revolution. Two major follow ups were the Barani Commission of 1975 led by Dr. Z.A. Hashmi and the 1986 Agriculture Commission led by Mr. Sartaj Aziz. All Five-Year Plans and numerous ministerial documents have been produced. The earlier plans focused on self-sufficiency in staple and in the post 1988 era, diversification has remained a focus of debate. Despite surplus staple, we have rampant malnutrition and rising rural poverty. With the recurrent failure of cotton crop and that of wheat in the current season, a new agricultural paradigm must emerge.

This Webinar Episode has analyzed successes and failures of the past and attempted to carve a innovative pathway for the future. The ultimate aim of the Webinar is to promote for a competitive, profitable and sustainable agriculture sector in Pakistan. Sixty-five participants logged in and joined the Webinar.

The discussion was held in the presence of and participation by a distinguished panel including Mr. Sartaj Aziz, Former Federal Minister of Finance/Agriculture/Foreign Affairs, Islamabad; Dr. Akmal Hussain, Dean Social Sciences, ITU, Lahore; Dr. Nadeem ul Haq, Vice Chancellor PIDE, Islamabad; Dr. Pervez Amir, Director Water Alliance, Islamabad and Dr. Mubarik Ali, Former CEO-PARB and Member Planning Commission, Islamabad.

The discussants included: Dr. Yusuf Zafar, Former Chairman PARC; Dr. Gu Wenliang, Agriculture Commissioner, China Embassy, Islamabad; Dr. Manzoor Soomro, Chairman ECOSF, Islamabad; Prof. Waqar Akram, IBA Sukhar ; Mr. Afaq Tiwana, Farmers Association of Pakistan and MS Rabia Sultan, Progressive Farmer, Muzaffargarh.

The opening agenda of the Webinar is summarized in Figure 1. We have a burgeoning population to feed while creating economic opportunities for the masses. We need to adapt and adopt technology, create transparent, fair and equitable markets and regulate/deregulate as appropriate, without tempering the terms of trade to the disadvantage of the farming sector.

Dr. Asif Kamran highlighted major issues in the crop sector and linked successes and failures of the sector to the formation and implementation of different policies or the mechanisms used to implement these policies.

Crop sector in Pakistan is characterized by low productivity per unit of land and water, poor quality (both nutritional and fiber quality), stagnated or declining yields, little diversification with 90% land and water devoted to 5 major crops (viz. Wheat, Rice, Cotton, Sugarcane, Maize). The sector performance is further threatened due to climate change, deteriorating infrastructure, and over exploitation and contamination of groundwater. Dr. Kamran attempted to explain the poor agricultural outlook of the area once famous as ‘grain basket of the sub-continent’ and later known as the most successful example of the Green Revolution (GR) in the 1960s.

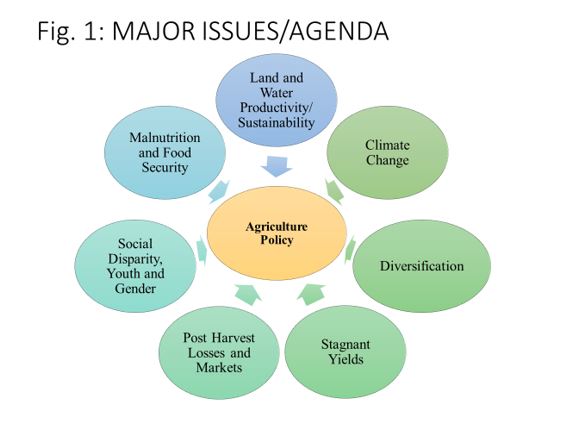

At the time of the independence in 1947, more than 90% people in Pakistan were in rural areas with agriculture contributing about 50% of the national GDP (Gross Domestic Product). In three successive 5-years plans from 1955-1970, more than 10% of the budget was allocated for the agriculture sector. Efforts were made to build agriculture supporting institutions like WAPDA (Water and Power Development Authority) to provide uninterrupted water supplies by building infrastructure and storages. The institutional credit system was also developed by establishing the Agricultural Development Finance Corporation in 1952 and Agricultural Bank of Pakistan in 1957 (both merged to become Agricultural Development Bank of Pakistan in 1961 and converted to Zarai Tarqiati Bank Limited in 2002). Research and Development (R&D) and academic institutions (NARS-National Agriculture Research System) were also built and strengthened to help adapt GR technologies in the local environment and their dissemination. It was through these institutions and their overwhelming support that Wheat and Rice showed tremendous yield gains in 1960s (Figure 2) that translated into agricultural GDP growth rate of 3.6% per annum during 1960-1965, and of 6.5% per annum during 1965-1970.

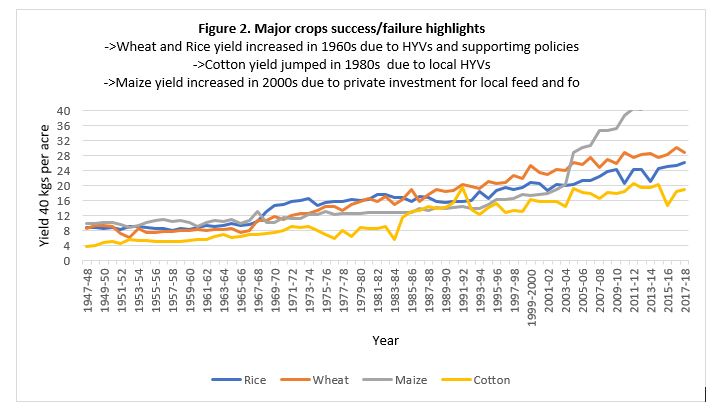

Meanwhile, the investment in local R&D started paying the dividend in form of high yield and input responsive locally evolved cotton varieties (NIAB-78 one of the most popular varieties developed at Nuclear Institute for Agriculture and Biology, Faisalabad in 1983) to break the yield stagnation in cotton in Punjab and Sindh during 1980s (Figure 2). These new heat tolerant cotton varieties could be planted after wheat that helped increasing the area under cotton exponentially and creating a new cropping pattern. Sugarcane was provided price support under the protectionist policy and in the absence of any improved genotypes the success of sugarcane since 1960s has been merely due to expansion in its cultivated area (Figure 3).

Source: Agricultural Statistics (various versios)

Later, new institutions like Pakistan Agriculture Research Council (PARC) and Agricultural Prices Commission (APCOM) were founded to provide R&D and policy support to the agriculture sector. Therefore, the success story of Pakistan’s agriculture in 1960s-1990s is a success of 4 crops only (i.e. wheat, rice, cotton, and sugarcane) mainly due to higher use of inputs and expansion in cultivated area. The gains up to 1990 were sustained during the 1990s.

The stagnation in production during 2000s is result of the withdrawal of government’s financial support, poor terms of trade, poor performance of the agricultural R&D innovation system and malfunctioning of agriculture markets. Maize is an exception among the success in the crops sector where commercial interest of food and poultry feed industries encouraged the introduction of imported hybrid seed along with ensuring the maize procurements. Success in high value fruit crops was mainly due to the area expansion of Kinnow mandarin coupled with the access to foreign markets. There is however a steady growth in the area and production of major fruits and vegetables. Potato is another sterling example of innovative growth.

Besides crops sector, poultry provides an example of success story where policy support by government in the form of income tax exemption, tariff free import of equipment, two meatless days in a week, generous credit facility to establish poultry feed and breed facilities resulted in a vibrant and high profit poultry industry.

The minor crops (fodders, pulses and oilseeds) remained stunted during the agricultural growth decades. The major reason is that there was no major progress on genetic improvement of these crops in the NARS and international agriculture research systems where the importance of rice and wheat staple hindered any effort to promote other crops. This neglect has severely impacted agro-ecosystem health due to lack of legumes in the crop rotations. As a result the yields of pulses and oilseeds stagnated at a very low level (Table 1).

Table 1: Stagnant Yield of major pulses and oilseeds since 1947

(40 kgs per acre)

| Year | Pulses | Oilseeds | |||||

| Chickpea | Masoor | Mash | Moong | Sesame | Linseed | Rapeseed | |

| 1947-48 | 5.34 | 5.32 | 4.75 | 3.58 | 3.46 | 4.17 | 4.06 |

| 1957-58 | 5.45 | 3.88 | 3.61 | 3.23 | 2.34 | 4.55 | 4.25 |

| 1967-68 | 4.27 | 3.24 | 4.89 | 4.36 | 2.85 | 5.56 | 5.04 |

| 1977-78 | 5.65 | 3.79 | 5.2 | 4.76 | 4.03 | 5.54 | 5.79 |

| 1987-88 | 4.58 | 4.11 | 4.73 | 4.66 | 4.05 | 5.28 | 7.68 |

| 1997-98 | 7.04 | 5.79 | 5.33 | 4.6 | 4.47 | 5.75 | 8.69 |

| 2007-08 | 4.34 | 4.86 | 5.39 | 7.32 | 4.34 | 6.76 | 7.98 |

| 2017-18 | 3.36 | 4.76 | 4.76 | 7.6 | 4.33 | 7.95 | 10.62 |

Source: Compiled from Agricultural Statistics

Dr Kamran discussed that after the 18th amendment of the constitution of Pakistan in 2010, agriculture became provincial subject though food security remained with the Federal government. The devolution of agriculture ministry to provinces and food security & research as federal subject demanded definition of the role of provinces and the federal government. That was followed by Federal National Food Security Policy, Provincial Agricultural Policies, Climate Change Policy, Disaster Management Policy, National/Provincial Water Policies and Livestock Policies. The major issues with these policies is the lack of implementation strategy and linkages between food security at the Federal level and agriculture at the provincial level along with the lack of intersectoral linkages and connections across the Agriculture, Water, Climate Change, and Disaster Management areas. Despite the known fact about the influence of the macroeconomic policies and national economic planning, the issue is not properly deliberated in the policy documents to ensure enabling macroeconomic environment for the sector. The perennial fiscal deficits and balance of payments, resulting in IMF packages, have almost always been perverse to the agriculture sector. The most important lesson from the success story and high growth of 1960s is that availability of technology and enabling policies are key for any growth in the agriculture sector. The policies are only good if they have good implementation mechanism. Else, they will not have significant positive impact, as was the case during the past two decades.

Dr Kamran concluded that the part of the blame for poor planning and implementation goes to poor state of local academic and applied research in general, and Social Science/Policy research in particular. Without involving the end user and interdisciplinary research, it is not possible to promote the sector and formulate viable policy options and implementation plans. As a way forward, it is important to learn from the past experience and promote small famers oriented crop diversification focused growth (as the proportion and area under small farms is increasing as shown in Table 2) with greater consideration for natural resources and nutrition sensitive agriculture.

Table 2: Farm Size/Land Distribution and Number of Farms (1960 & 2010)

| Farms composition | Below 5 acres | 5-12.5 acres | Below 12.5 Acres | 12.5-25 acres | Below 25 Acres | 25-50 acres | Above 50 acres |

| 1960 | |||||||

| No. of farms (%) | 50.7 | 27.8 | 78.5 | 14.7 | 93.2 | 5.4 | 1.4 |

| Farm area (%) | 10.9 | 25 | 35.9 | 28.5 | 64.4 | 20 | 15.6 |

| 2010 | |||||||

| No. of farms (%) | 63.8 | 26.72 | 90.5 | 7 | 97.5 | 1.84 | 0.64 |

| Farm area (%) | 22 | 36 | 58 | 20 | 78 | 10 | 12 |

Source: GoP, 1960 & 2010

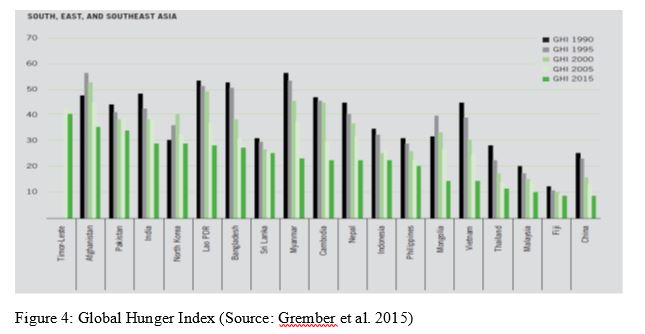

Dr M Ejaz Qureshi delivered a keynote on ‘Policies for a strong agriculture sector in Pakistan – moving from a subsistence to more profitable farming system’. In his presentation, Dr Qureshi told that the agriculture contribution to GDP is half of what was in early 1960s but still provides livelihood of about half of the country’s population, employing 24 million people. He also told that cotton, rice and leather plus cotton textiles and ready-made garments contribute about 38% of the total foreign (export) earnings. He argued that increased productivity in the agriculture sector helped the country in reducing hunger from about 45% in 1990s to a little over 30% in 2015 showing IFPRI Global Hunger Index (GHI) (Grember et al. 2015). He compared the GHI in Pakistan with Vietnam and showed that the level of decline in hunger in Pakistan is less than what (for example) happened in Vietnam where the country reduced its hunger from a similar level in 1990s to close to 10% in 2015 (Figure 4).

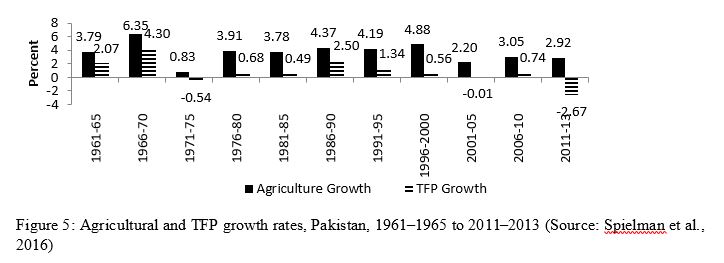

Dr Qureshi argued that one of the major factors of less decline in hunger in Pakistan is lack of greater agriculture sector productivity which is critical to reduce hunger and increase food security in the country. He showed that despite increase in the agriculture sector growth per annum in Pakistan in the last few decades by about 3%, the total factor productivity (TFP) did not increase during this period and in 2011-2013 it in fact declined by about 3% (Figure 5). This level of decline in TFP shows that the agriculture sector growth was not because of increase in the productivity but due to greater use of inputs (such as fertilizer and water) per unit of land.

He argued that despite the intensive use of inputs, the sector is facing several major challenges including stagnating crop yields with wide gaps between progressive and average farmers; declining investment including in research, development and extension; poor quality and inadequate supply of inputs and lack of infrastructure; under-performing or inefficient agriculture input & output markets; high pre and post-harvest losses; lack of international competitiveness of several agricultural commodities; little diversification and highly skewed distribution of farm size and low economy of size and scale. The irrigation sector was already facing inefficiency and salinity management issues and now climate change has exacerbated the problem. Pakistan is now considered water insecure, as its per capita water availability has decreased from 5,000 in 1947 to less than 1,000 cubic meters per person per year.

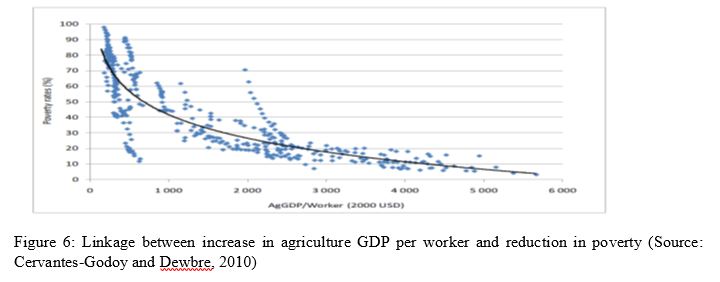

The increase in agriculture sector productivity is not only essential to increase food security but also critical for reducing poverty. Studies show strong correlation between increase in agriculture productivity, income generation and rural poverty reduction (Cervantes-Godoy and Dewbre, 2010; Mellor, 1966 & 2017). Thirtle et. al., (2003) showed strong impact of agricultural productivity growth on poverty reduction in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Their analysis as shown in Table 3 indicates that 1% increase in crop yield helped 2.51 million people with $1 per day income in South Asia. It also shows that to remove a person from poverty required $179 spending on research and development (R&D).

Table 3: Effect of 1% increase in crop yields on the number of people living on less than $1/day

| Region | Percentage in $ 1 per day poverty | Reduction in number in $1 per day poverty (millions) | R&D cost per person removed from poverty |

| East Asia | 15 | 1.34 | $179 |

| South Asia | 40 | 2.51 | $179 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 46 | 2.09 | $144 |

| Latin America | 16 | 0.08 | $11397 |

| Total | 24 | 6.24 | N/A |

Source: Thirtle and Piesse (2003)

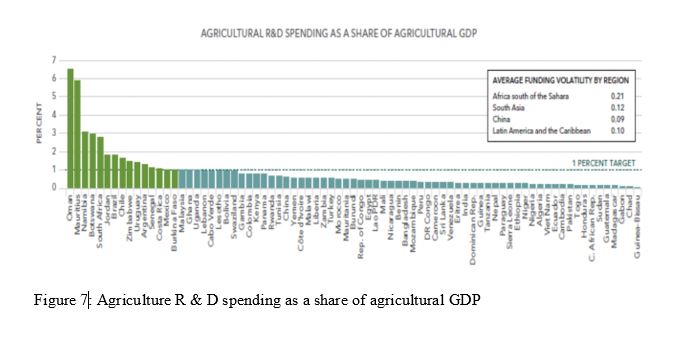

In Pakistan, total expenses on the research and development are less than 0.5% of the agriculture GDP and is lower than other South Asian countries, shown in Figure 7. Greater R&D spending can help in increasing agriculture productivity and reducing poverty from the country. Along with greater investment in R&D, increase in efficiency and productivity of major inputs (such as fertilizer and water) is essential.

Source: IFPRI (2017)

Agriculture markets are critical in reducing poverty from the country. Well-functioning agriculture markets can help both producers and consumers. They can improve household food security and provide greater comparative advantages over subsistence production. Strong local agricultural markets and value chains where suppliers are connected to farmers and farmers to consumers can accelerate inclusive growth and promote investment. However, in Pakistan, agriculture markets have not played the desired role. A recent ACIAR project on markets in Pakistan confirms that the agriculture markets could not achieve the key objectives of facilitating producers in a competitive environment and the consumer in purchasing agricultural produce at a fair price.

The above-mentioned project and its markets specific activity found that the legal framework for agriculture markets in Pakistan has been restrictive for private markets. It created barriers to entry, produced monopolies, restricted farmers’ freedom to sell their produce and enabled a layer of middlemen (Nadeem and Rana, 2020). One of the research activities of the project examined the agriculture markets in China and found that in China the agriculture markets are much more efficient. The researchers argue that one of the reasons of more efficient agriculture markets is greater consolidation and specialization of markets which created a strong link between producers and markets (Huang and Ali, 2020). The researchers also argue that the major driving forces which facilitated agricultural growth in China included institutional reforms, policies related to technology markets and investment in agriculture. Further, they argue that these reforms helped in improving efficiency of resource allocation, facilitated agricultural structural change and helped producers in cheaper input prices and higher output prices.

Based on the above findings and observations, it is clear that more investment is needed in research and development to increase crop yields and the sectoral productivity. Also, appropriate agricultural policies are warranted to facilitate markets which can provide clear signals for both producers and consumers. Once these signals are clear then producers will produce what is required knowing in advance how much consumers are willing to pay and consumers will know where to get the best produce and increase value for their money. It will require a paradigm shift away from subsistence farming towards a more commercially oriented farming, which is profitable and attractive for farmers to continue farming.

Dr. Mubarik Ali discussed his work on value chain development where 23 commodities were analyzed. He argued that except sugar, all of our commodities are selling below the average international/export prices. The farm gate prices of commodities in Pakistan are still very low compared to the international averages but losses occurring in the supply chain makes them costlier. He suggested promotion of SMEs for value addition, training/capacity building and supply of credit could bring a positive change.

Dr. Pervez Amir analyzed the shift from five major crops to livestock, minor crops (minor not in significance but acreage) and fisheries. He proposes to improve the management of farming as enterprises which involves taking production and marketing decisions i.e. what to produce. He thinks that the price makes the farmer work. He was critical of extension services being ineffective for not helping the farmer’s decision making process. He argued that import substitution is as much of importance as is export and quoted examples of canola as rabi crop which also save water. Water has been a primary determinant of agricultural growth and efficiency. A future threat to agriculture would be lack of interest on the part of families and youth to consider agriculture as a profession. Climate change and environment deserve a better planning for farm forestry and peri urban plantations. The opportunity lies in making best use of CPEC markets and technology transfer, considering China and Israel as the Technology Power Houses. That can make agriculture truly an engine of growth with a potential to rise from 50 to 350 billion dollars.

Dr. Yusuf Zafar lamented the lack of political will. The policies remain a piece of paper without a charter of development for agriculture. Ms. Rabia Sultan echoed the sentiments expressed by Dr. Zafar. She thought the successive governments have shown no ownership for the agriculture sector and didn’t give it a priority the sector deserved. Dr. Manzoor Soomro expressed a need for complementation between agricultural education and practice (technology) and proposed farmers’ education on farmers’ field school model. Dr. Waqar Akram responded to the concern raised by Dr. Amir about Youth in Agriculture and future human resources meant for the sector with loyalty to agriculture. He explained the 2+2 BBA degree program jointly launched by SIBA and UAF where students from rural background are being admitted from two provinces (Sindh and Punjab). They are educated in agriculture for two years at UAF and then two years in business and economics at SIBA.

Dr. Akmal Hussain was critical of policy bias for elite where small farmers are always ignored. Land fragmentation has been a continuous process, reducing the farm size and increasing the number of farms (Table 2). That erodes the capacity of the farmer to adopt/adapt technology and to innovate. The outreach opportunity of public extension and delivery of services are compromised and expensive.

The inabilities of the small farmers and the state together have translated into a stagnant productivity and lack of profits in agriculture. Along with absorption of production technology, the small farmers must be enabled to add value. There is a huge supply and demand gap in the milk as an essential commodity in the region. Raising milch animals and improvements in the milk supply chain could be a strong poverty alleviation element. The Industrial/Agricultural Development Corporations of Pakistan were created in the 1960s. A similar model i.e., a Small Farmers Services Corporations is a possible solution. A new Charter on Agriculture Policy is being emphasized.

Dr. Nadeem Ul Haq caped the discussion in following four points/prescriptions:

- The policy of huge expectation from government is not likely to work because of her own indebtedness.

- Agriculture is spoiled with love for incentives and subsidies that kills urge for innovation and competition.

- Agriculture needs to become a business and for that we need markets and technology. Markets are limited in infrastructure and marred by poor governance.

- Era of talking compassion for the small farmers should be over. Land markets should be developed, and agriculture mechanized through services. Invest in skill and let the surplus labor migrate away from agriculture.

Mr. Sartaj Aziz concluded the session with his appreciation for a time well spent on a substantive discussion. The take home messages he gave are summarized in the following.

- Policies fail because of lack of How and Who (ownership). Many a times legislative support is missing. In general, the role of government is around 20% and rest is the stakeholdership. But, that 20% part of the policy prescription and implementation makes the difference.

- Terms of Trade usually work against the farming sector, making agriculture policies irrelevant. Parallel to agricultural thought process are the fiscal policy, exchange rates, trade barriers and SROs. The 2009 Food Security Report envisages a biennial calculation of terms of trade of agriculture and bring it to the council of common interest and other high power forums directly and through media (API or PIDE or provincial institutions to be entrusted).

- Animal Feed industry needs to be focused to make it adequate to enhance milk and meet productivity and fulfil nutritional demand.

- A serious observation is about the decline of institutions with exit of individuals. Today, we cannot name a single first rated institution in the country that can be enlisted as a globally competitive Think Tank or a technology Powerhouse. Examples of Dr. Qureshi (wheat), Dr. Mehboob (cotton) and Dr. Majeed (rice) were quoted. Besides research institutions, marketing institutions need to be emphasized for improvement.

- Agriculture Policy should be compatible with the Climate and Water Policies. Water productivity in agriculture need to be improved and there is an urgent need to implement National Water Policy of 2018.

- Hopes are pinned on a newly formed Agriculture Committee of CPEC. Coupling of Chinese institutions with Pakistani institutions can help our institutions and promote exports to China.

The audio/video recording of the event is available at the webpage of PAS www.paspk.org; www.uaar.edu.pk and at a YouTube link: https://youtu.be/sZCjSrXraag

As a summary of the session, following observations and strategic policy recommendations have emerged:

- There is no dearth of agriculture policy prescriptions. The analysis of success stories of green revolution (1960s), poultry (1970s) and cotton (1980s) revealed a combination of policy environment where enablement and market forces led to the absorption of technology.

- The growth analysis correlates with investment in the agriculture sector in infrastructure, technology transfer and income generation.

- The stagnation in the 2000s is not because of lack of policy prescription but more due to lack of ownership, obsoletion of technology and market manipulations. The Terms of Trade have remained unfavorable to agriculture.

- Diversification of the sector has remained elusive and natural resource degradation is unabetted. The cultivated area required for diversification has to be spared by achieving higher productivity of five crops, particularly wheat and cotton.

- The urban/rural disparity, malnutrition, poverty and other inequalities (gender and youth) have started to dominate the discussion because of lack of performance in the agriculture sector. That is further compounded by the Climate Change and social unrest.

- The discussion of small farmers as a unit of production versus treating agriculture as a business is becoming a topic for intellectual input. That requires another level of political and socio-cultural discourse.

- A new charter of agricultural development must emerge through an open debate for legislation to promote innovation and entrepreneurship.

- While good governance is a key element, that must not come through over regulation. Instead, we should support participatory actions.

- The investment in research and human resource development has considerably declined during the past two decades. A horizontal spread of institutions has thinned out the available human resource.

- Independent analysis and reports are needed to achieve a constant course correction. For that to happen, a greater revamp of federal and provincial institutions and innovation ecosystem is required with the consensus of the stakeholders.

Acknowledgement: Web services were provided by Mr. Shehzad Ashraf and Mr. Muhammad Naseer. Webinar design, illustrations, announcements, registration, feedback and analysis, and editorial assistance by Mr. Nehal Ahmad Khan. This write up is a tribute to Mr. Sartaj Aziz for his services to the nation in general and to agriculture in particular.